Uterine Fibroids (UF), also known as Leiomyomas (Navarro et al., 2021), are the most common benign tumours in the pelvis of women of childbearing age worldwide. They affect roughly 70% of women in the world, with Black or African-American women being the most affected (Al-Hendy et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2021; Menson et al., 2024). Despite the widespread prevalence of this condition, many women still suffer from its symptoms daily. Uterine fibroids vary in shape and size; each one has a very different composition from the next, making it significantly difficult to manage them. What may work for one fibrotic tumour may not work for another. This becomes increasingly difficult when women have rapidly growing and large fibroids. If their fibroids are unresponsive to medical treatment, the next treatment option is surgical intervention, which doesn’t prevent the possibility of another fibroid developing in the future. With all of this in mind, it is important that more people know about fibroids and that more research is conducted to identify appropriate and effective treatments for this condition (Yang et al., 2021; Menson et al., 2024).

What exactly is a fibroid?

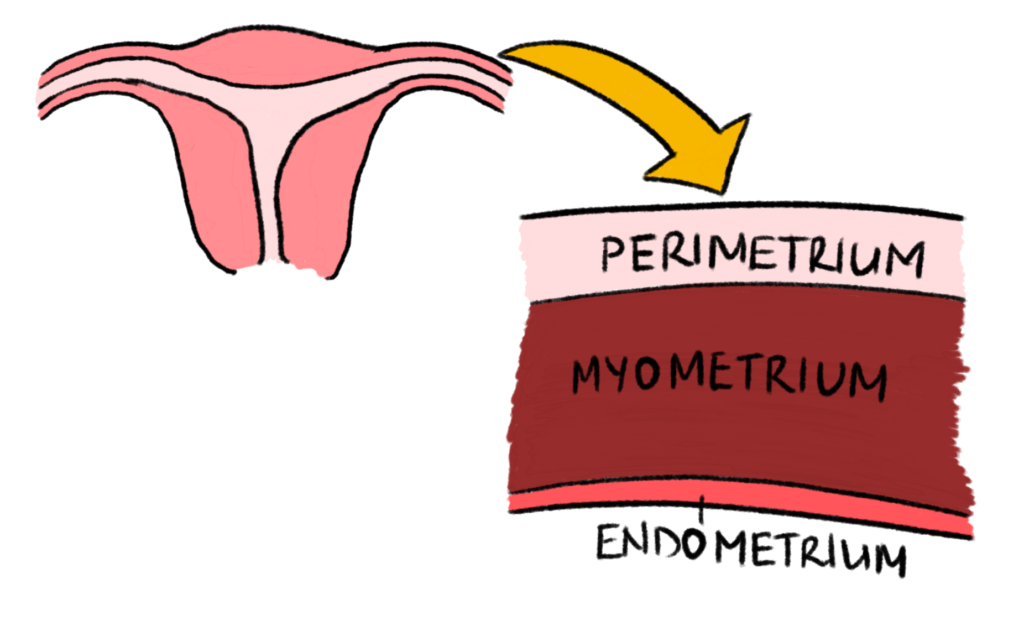

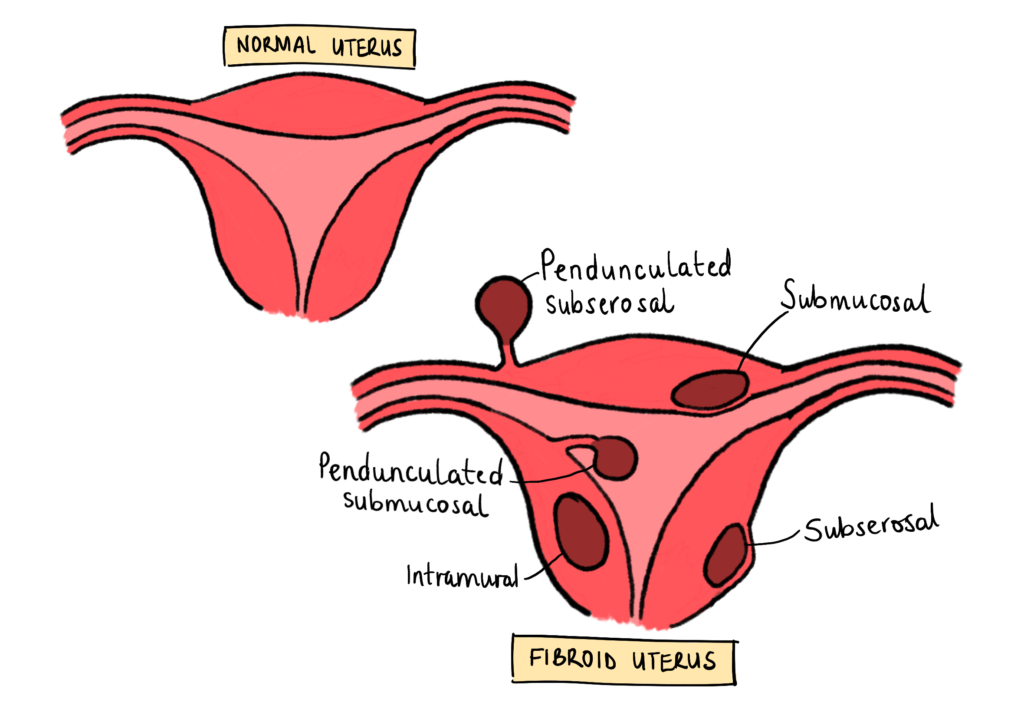

The wall of the uterus is mainly made up of three layers – the perimetrium (also sometimes referred to as the Serosa), the Myometrium, and the Endometrium. Fibroids are smooth muscle tumours that build up in the Myometrium, which is the muscular wall of the uterus [Figure 1]. Fibroids can grow anywhere in that muscle wall, and sometimes, depending on where they grow, they can be very disturbing and cause significant symptoms, which may even be unrelated to the female reproductive system. Figure 2 shows the different types of fibroids and where they typically grow.

Figure 1 – Layers of the Uterus Wall: This diagram shows the layers in the wall of the uterus as mentioned in the article. Created by Mojibola Orefuja (author).

Figure 2 – Classification of Uterine Fibroids: This diagram shows the different places and types of fibroids that can grow within the uterus. Created by Mojibola Orefuja (author).

What can cause fibroids to form?

To understand some medical treatments for UF, it is helpful to understand the physiological processes that can lead to the formation of the uterus. For a long time, many believed that fibroid formation was linked only to oestrogen and progesterone, and while many studies have shown that oestrogen and progesterone have a significant effect on fibroid growth, they may not trigger the initial formation of fibroids (Bulun et al., 2025). We know this because fibroids tend to grow during a woman’s childbearing years, but as soon as menopause occurs, the fibroids begin to shrink. Many studies have even confirmed that oestrogen stimulates activation of progesterone receptors, which is key in the growth and development of fibroids (Menson et al., 2024).

Additionally, more studies have shown that many other biological and chemical factors can lead to the formation of fibroids. A key growth factor involved in the proliferation and remodelling of the endometrium during the menstrual cycle, Tumour Growth Factor-beta (TGF-B), has been found to be upregulated in uteruses with fibroids, and also has been associated with abnormal signalling within the fibroid uterus (Norian et al., 2009), thus suggesting that this factor can contribute to the development of fibroids. Many other biological and inflammatory factors have also been implicated, including TNF-alpha, IL-33, IL-8 and MCP-1.

All of these factors are thought to contribute to the development of fibroids by stimulating normal uterine stem cells to differentiate into abnormal fibroid smooth muscle cells with increased extracellular matrix, rather than developing into the normal myometrial smooth muscle cells for which they were produced (Menson et al., 2024; Bulun et al., 2025).

Do you have risk factors for uterine fibroids?

There are many external factors that can increase the risk of developing fibroids, as well as numerous internal factors that can lead to their development. As mentioned above, Black and African-American women are the most affected group of women when it comes to Uterine Fibroids; however, there are very few studies which provide an explanation for why this is the case (Yang et al., 2021; Eltoukhi et al., 2015). Other external factors which can put one at a higher risk of developing fibroids include:

- increased age

- being pre-menopausal

- having had no children

- a family history of fibroids

- high blood pressure

- obesity

- vitamin D deficiency,

- even certain foods, such as soybean milk (Yang et al., 2021).

What are the symptoms of fibroids?

For many people, they can live with their fibroid without significant concern or it affecting their lives, while for others, having a fibroid can be severely life-changing. Some of the symptoms that women with fibroids experience include (Behairy et al., 2024):

- heavy menstrual bleeding, which can lead to anaemia and anaemia symptoms like dizziness, shortness of breath and pallor

- significant abdominal pain, both during and not during periods

- constipation

- urinary frequency (going to use the toilet very often), or

- urinary retention (urine getting trapped in the bladder and not being able to get it out)

- difficulty getting pregnant, or infertility

Many of these symptoms are not directly caused by the fibroids in the uterus, but rather by a very large fibroid mass that pushes on the bladder or rectum (the backend).

How are fibroids diagnosed?

As uterine fibroids are a physical structure within the pelvis and uterus, it is very simple to diagnose someone with them, because you only need an imaging form. The first option, which is often enough to diagnose fibroids, is a Transvaginal Ultrasound Scan. This is an ultrasound scan, which has a probe inserted directly into the vagina to visualise the uterus very clearly. It is an effective method for identifying many structural concerns throughout the female reproductive system (Menson et al., 2024).

Doctors may use other methods to investigate and manage fibroids, as ultrasounds don’t always provide clear information about a fibroid’s location within the uterus, its attachment to the uterus, etc. Other modes of investigation include:

- Hysteroscopy – Using a small camera inserted into the uterus through the vagina, to assess whether there are structural abnormalities, including fibroids, within the uterine cavity. This isn’t always used because it is an uncomfortable procedure, and although it is very clear during the procedure, it can be very difficult to refer back to different things seen in the uterus without having taken pictures. This makes it much harder for doctors to make subsequent plans based on hysteroscopies (Menson et al., 2024).

- MRI Pelvis- This is a high-resolution imaging modality that allows for more precise visualisation of the uterus from outside the body. With this method, there is no pain, and you can refer back to clear images even after the procedure.

How are fibroids treated?

When deciding how to treat and manage a fibroid, many different factors need to be taken into consideration:

- How big is the fibroid?

- Where is it located?

- Is it just one or multiple?

- What are its associated symptoms?

- Are they affecting the patient’s quality of life?

- Can the symptoms be managed with medication?

- Is the patient still hoping to have more children?

- What are the chances of the fibroid recurring?

And there are many other unique considerations for each woman that their doctors have to consider. Once this is established, most treatments for fibroids can be divided into medical and surgical options.

Tranexamic Acid – This medicine can help reduce abnormal or heavy bleeding, which is common in women with fibroids. It is an antifibrinolytic medication, which means it helps blood clot, slowing and reducing heavy bleeding (Menson et al., 2024).

Intrauterine Device – This is a progesterone-only coil implant with Levonorgestrel. This hormone is used because studies have shown it can reduce fibroid cell proliferation and possibly trigger cell death. However, no studies have confirmed that Levonorgestrel can be used to “shrink” fibroids, so this treatment is only used to manage abnormal bleeding (Menson et al., 2024).

Ulipristal Acetate – This is a selective progesterone receptor modulator, which means that it affects progesterone’s influence on fibroids. Courtey, Donnez and Dolmans (2015) conclude that this medication has a clinically significant effect on reducing fibroid size and volume by inhibiting cell proliferation, inducing cell death, and remodelling the extracellular matrix in which fibroids develop.

Combined Oral Contraceptives – These have been effective in reducing fibroid symptoms as they can help with abnormal bleeding and also with pain management. Unfortunately, they are not available to all women due to contraindications and lack beneficial effects in many women (Menson et al., 2024).

GnRH antagonists with addback therapy – An example of these medications is a medication called Ryeqo. More about this later in the article.

Surgery – the type of surgery suggested is dependent on whether the woman has had all the children she wants to bear.

- Myomectomy – this is a surgery to remove just the fibroid, given that it is located where it can be removed. This is a very risky surgery as fibroids are very vascular structures, and so when removing them, there can be significant blood loss as a complication. Also, having one myomectomy does not confirm that another fibroid will not grow in the uterus again.

- Hysterectomy – this is the complete removal of the uterus. This is only suggested in women who have had children and do not wish to have any more. This surgical option is indeed the most effective for fibroids, as it removes the site where they can grow and confirms that they won’t grow back.

What is Ryeqo?

Ryeqo is the name of a new combination medication used to treat many different gynaecological conditions. The medications in Ryeqo include Relugolix, with additional add-back therapy: estradiol (a synthetic form of oestrogen) and norethisterone (a synthetic form of progesterone).

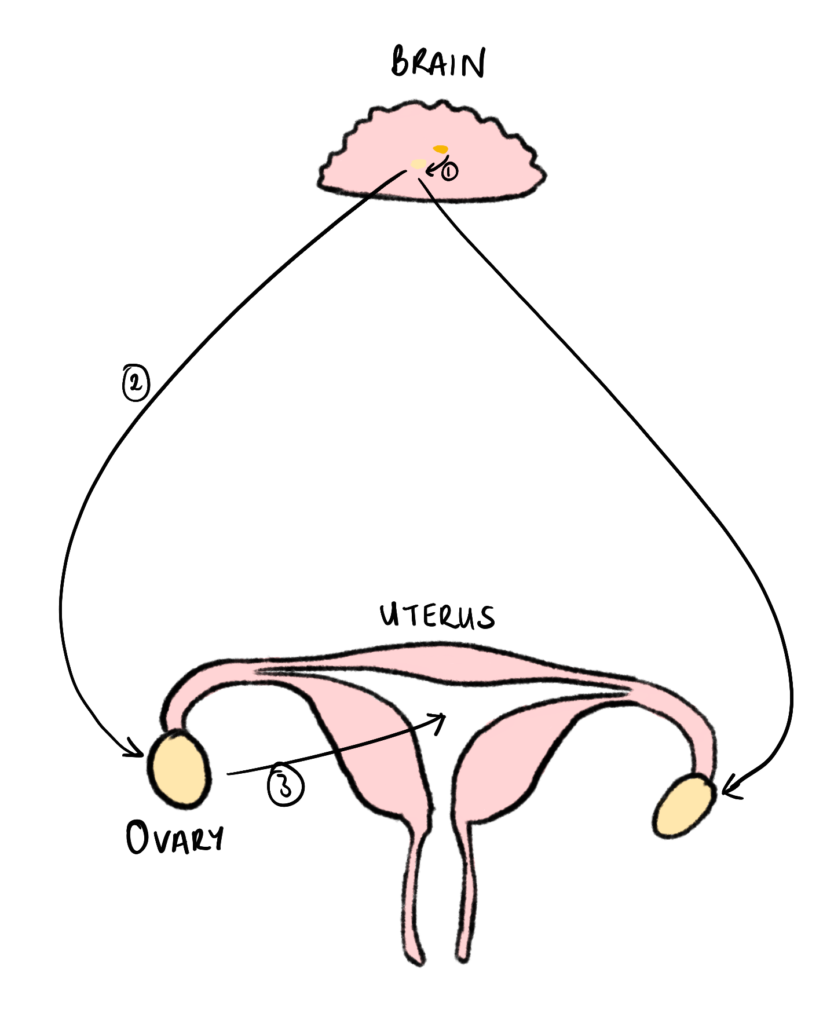

Relugolix is a GnRH receptor antagonist. GnRH (Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone) is a hormone released from the Hypothalamus, which binds to receptors in the anterior pituitary gland in the brain. It stimulates the release of 2 hormones from the anterior pituitary gland called Luteinising Hormone (LH) and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH). This results in the release of oestrogens and progesterones in the ovaries and parts of the uterus [Figure 3].

Figure 3 – GnRH Pathway: This diagram shows the pathway of stimulation for GnRH, from the anterior pituitary gland to the uterus:

(1) Release of GnRH from the hypothalamus to the anterior pituitary gland.

(2) Release of LH and FSH from the anterior pituitary gland to the ovaries.

(3) Release of Oestrogen and Progesterone to the uterus. Created by Mojibola Orefuja (author).

When GnRH receptors are blocked by antagonists like Relugolix, this process does not occur, leading to very low levels of oestrogen and progesterone in the body. This is good for fibroid management and its symptoms, because, as we have already established, oestrogen and progesterone have growth-promoting effects on fibroids (Syed, 2022).

However, by reducing the body’s normal levels of oestrogen and progesterone, significant side effects may arise, including reduced bone mineral density, hot flashes, and elevated blood lipid levels. Ryeqo combats this by including “add-back therapy” of synthetic oestrogen and progesterone at lower doses, so we can maintain an acceptable concentration of oestrogen and progesterone sufficient to support normal body functions without overstimulating fibroid growth. Norethisterone is a synthetic form of progesterone at very low levels to protect the uterus from unwanted effects and risks of oestrogen (Syed, 2022).

Hoshai et al (2021) conducted a Phase 2 clinical trial that concluded that Relugolix had a statistically significant effect, resulting in a reduction of heavy menstrual bleeding in women with fibroids. These effects are dose-dependent, with the highest-dose test of Relugolix 40mg being most effective, in which 83.3% of women on this dose achieved the primary end point (reduction in heavy menstrual bleeding). In a phase 3 trial (Osuga et al., 2019), Relugolix was found to be non-inferior to some current treatments, suggesting it has similar benefits to established treatments. In Black or African-American women, Relugolix has also been found to be very effective in managing heavy menstrual bleeding according to Stewart et al (2024), as this study shows 82.% of women enrolled in the study had a substantial reduction in menstrual blood loss. They also experienced fewer side effects of reduced oestrogen levels, with minimal hot flushes and maintained bone mineral density.

These results show that Ryeqo is likely to be transformative in the treatment of fibroids, with significant symptom management and reduced historical side effects.

References:

Al-Hendy, A., Myers, E.R., Stewart, E. (2017) ‘Uterine Fibroids: Burden and Unmet Medical Need’, Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 35, pp. 473-480.

Behairy, M.S., Goldsmith, D., Schultz, D., Morrison, J.J., Jahangiri, Y. (2024) ‘Uterine fibroids: a narrative review of epidemiology and management, with a focus on uterine artery embolization’, Gynaecology and Pelvic Medicine, 7(23) pp. 1-17.

Bulun, S.E., Yin, P., Wei, J., Zuberi, A., Iizuka, T., Suzuki, T., Saini, P., Goad, J., Parker, J.B., Adli, M., Boyer, T., Chakravarti, D., Rajkovic, A. (2025) ‘Uterine Fibroids’, Physiological Reviews, 105(4) pp. 1947 – 1988.

Courtoy, G.E., Donnez, J., Marbaix, E., Dolmans, M.M. (2015) ‘In vivo mechanisms of uterine myoma volume reduction with ulipristal acetate treatment’, Fertility and Sterility, 104(2) pp. 426-434.

Eltoukhi, H.M., Modi, M.N., Weston, M., Armstrong, A.Y., Stewart, E.A. (2015) ‘The health disparities of uterine fibroid tumours for African American women: a public health issue’, American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 210(3) pp. 194-199.

Hoshiai, H., Seki, Y., Kusumoto, T., Kudou, K., Tanimoto, M. (2021) ‘Relugolix for oral treatment of uterine leiomyomas: a dose-finding, randomized, controlled trial’, BMC Women’s Health, 21(375) pp. 1-11.

Menson, E., Calaf, J., Chapron, C., Dolmans, M.M., Donnez, J., Marcellin, L., Petragalia, F., Vannuccini, S., Carmona, F. (2024) ‘An update on the management of uterine fibroids: personalized medicine or guidelines?’, Journal of Endometriosis and Uterine Disorders, 7, pp. 1-7.

Navarro, A., Bariani, MV., Yang, Q., Al-Hendy, A. (2021) ‘Understanding the Impact of Uterine Fibroids on Human Endometrium Function’, Frontiers in Cell and Development Biology, 25(9) pp. 633180.

Norian, J.M., Malik, M., Parker, C.Y., Joseph, D., Leppert, P.c., Segars, J.H., Catherino, W.H. (2009) ’Transforming Growth Factor β3 Regulates the Versican Variants in the Extracellular Matrix-Rich Uterine Leiomyomas’, Reproductive Sciences, 16, pp. 1153–1164.

Osuga, Y., Enya, K., Kudou, K., Tanimoto, M., Hoshiai, H. (2019) ‘Oral Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonist Relugolix Compared With Leuprorelin Injections for Uterine Leiomyomas: A Randomized Controlled Trial’, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 133(3) pp. 423-433.

Stewart, E.A., Al-Hendy, A., Lukes, A.S., Madueke-Laveaux, O.S., Zhu, E., Proehl, S., Schulmann, T., Marsh, E.E. (2024) ‘Relugolix combination therapy in Black/African American women with symptomatic uterine fibroids: LIBERTY Long-Term Extension study’, American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 230(2) pp. 237.

Syed, Y.Y. (2022) ‘Relugolix/Estradiol/Norethisterone (Norethindrone) Acetate: A Review in Symptomatic Uterine Fibroids’, Drugs, 82, pp. 1549–1556.

Yang, Q., Ciebiera, M., Bariani, M.V., Ali, M., Elkafas, H., Boyer, T.G., Al-Hendy, A. (2021) ‘Comprehensive Review of Uterine Fibroids: Developmental Origin, Pathogenesis, and Treatment’, Endocrine Reviews, 43(4) pp. 678-719.