Over the last few months, it has become more and more apparent to me that despite numerous studies and constant research which discuss the very real issue of depression, people still think it is a made-up condition. I come from a cultural background that has found ways to dismiss mental illness through statements like “our grandparents and parents never had these problems”, “this is the consequence of living a comfortable life”, or “this is a Western world problem”. I despise this take. From the point of view of a healthcare professional, these statements erase the lives and suffering of people who do have depression, and prevent them from seeking the help they desperately need. From the point of view of a person who has experienced depression myself, it reinforces the sadness and isolation that comes with the condition.

In order to begin the conversation of change around depression in my culture, I am turning to my strongest weapon – my love of research. In this article, I would like to clearly show what depression is and how we define it. I will also discuss some of the different forms of depression and how the function of our brain can actually be linked to it. I hope this article reaches the right people to start a shift in mindset and show people that depression is not made up, and people suffering from it deserve our support and respect.

What is Depression?

According to NICE UK, depression is defined as:

“low mood, a loss of pleasure or interest in everyday activities and hobbies, and a range of other associated physical and biological symptoms (1)”.

There are different types of depression, each with distinct influences and symptoms, but they all share the definition above.

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD)

This is the most common type of depression. On average, 14.6% of the adult population in high-income countries will experience depression at some point in their lifetime (2). That’s roughly 1-2 people per group of 10. Imagine attending a small family gathering or a dinner party with friends, where among the ten people present, one or two silently endure the burden of depression. This prevalence brings to light the shared reality, underscoring the importance of awareness and compassion for those around us who may be struggling.

Some symptoms of MDD include:

- chronic low mood, which is described as sadness

- loss of pleasure and hope, which is often described as numbness

- loss of energy and appetite

- poor concentration

- feelings of worthlessness or guilt

- feeling excessively tired, or not tired at all

- suicidal thoughts

Psychiatrists conduct a mental health assessment to determine whether patients have the above symptoms in order to diagnose them. You don’t have to show all these symptoms, but there is an established criterion that has to be fulfilled for you to receive an official diagnosis for depression (3). With this type of depression, the symptoms must be present for more than 2 weeks, and the patient must not have any other history of elated or extreme positive mood, sometimes known as Mania or Hypomania. If this is present, this would be diagnosed as a different type of depression/depressive condition called Bipolar Affective Disorder.

Bipolar Affective Disorder (BAD)

This type of depressive condition is characterised by 2 or more episodes of severe disturbance to a patient’s mood and activity levels. They either experience episodes of significantly elevated moods and energy levels, or episodes of extremely low mood and reduced activity levels (4). During episodes of Mania, people with this condition often show the following symptoms:

- extremely high self-esteem or self-worth

- rapid speech

- jumping through thoughts quickly while speaking

- difficulty concentrating

- irregular sleep

- reckless or risky behaviour

People with BAD will also experience episodes with symptoms of depression, as mentioned above (5). It is difficult to say how long patients with BAD are in these episodes for, as some of them can range up to years. Each experience of the symptoms of BAD is different for each person.

Perinatal and Post-partum Depression

This is defined as depressive symptoms during or up to 1 year after pregnancy. Roughly 10-13% of women who are pregnant and have just given birth experience perinatal depression worldwide (7, 8). These women experience many of the above symptoms mentioned in the section about MDD. There is a stigma around perinatal and post-partum depression, which is unfortunate, and we as a society need to do better by mothers to support them through this condition.

Mixed Anxiety and Depression

This form of depression is combined with another type of mental health condition called Anxiety (please see this link for more on Anxiety:https://staymeducated.com/im-overthinking-this-title-lets-talk-anxiety/). These symptoms combine to create very intense physical symptoms which are very difficult to live with (6).

Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD)

This is a recurring and cyclical type of depression that affects many people in the world. Patients with this type of depression go through seasons of intense depressive symptoms (mentioned above), which often resolve when the season passes, and then present themselves again when the season comes back around. For most people, the depressive symptoms occur during winter (9). It is very easy to try to dismiss this form of depression, but research has shown that there is a link between sunlight and the brain’s ability to produce adequate chemicals for normal mood control (9). I will discuss more about the brain’s role in mood control later in the article.

There are lots of different forms and types of depression, but these are the main forms to consider when thinking about depression.

Basic Brain Physiology

Now that we have discussed depression generally, I would like to go into some basic brain science to help build the picture. For the brain to function normally, it sends neurotransmitters along our neurons. These are chemicals which allow the brain to control which messages it sends to the body. The main neurotransmitter that is important to consider in Depression is Serotonin.

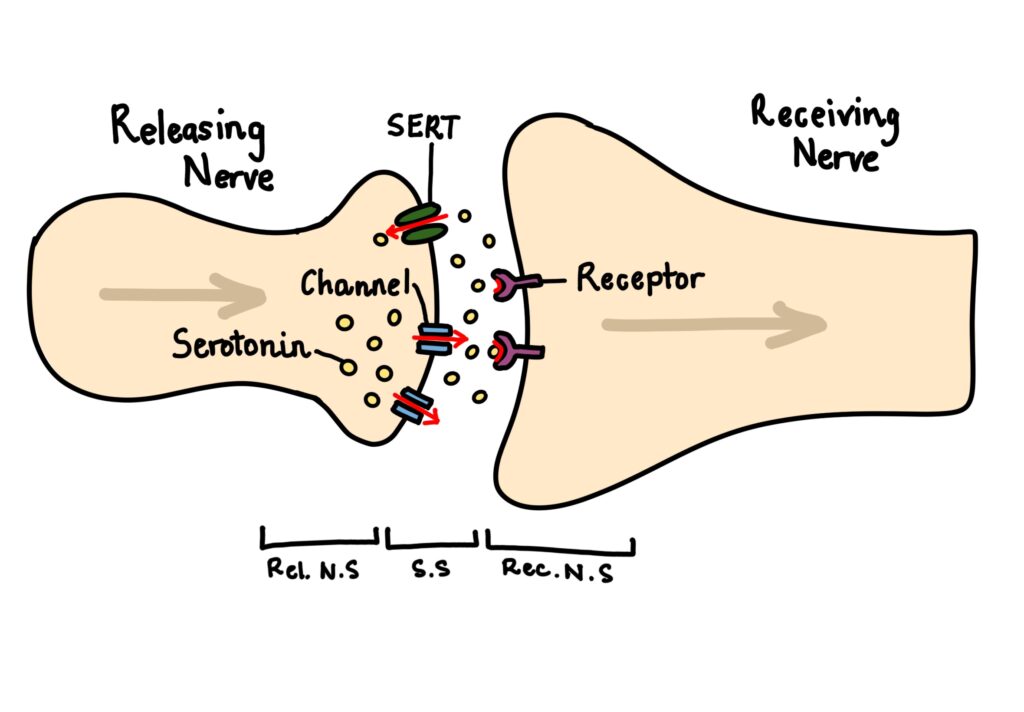

Serotonin is known as the happy hormone, because this hormone is most known for the effects it has on your mood (10). It allows us to build memories around happy situations, so that we feel happy again whenever we are back in them or when we think back on them. Although this is not its only function, it is a major one. Generally speaking, serotonin is transferred from one nerve to another from synapses, which are found at the tips of the nerves [Figure 1]. Serotonin is transferred from the releasing nerve to the receiving nerve through channels, and once the message is transmitted, the serotonin particles are returned to the space between the nerves. They are then returned to the releasing nerve via the Serotonin Transporter (SERT) (11).

Figure 1 – Serotonin Transport across Nerves: This diagram shows how serotonin is transported from one nerve to another, but then taken back up by the original nerve, to reduce the buildup of free serotonin in the brain. Rel.N.S. is Releasing Nerve Synapse; S.S. is Synaptic Space; Rec.N.S. is Receiving Nerve Synapse. Created by Mojibola Orefuja.

Brain Chemistry in Depression

While many factors can contribute to and lead to the development of Depression, brain biochemistry is a very well-explored factor that many people don’t actually understand. This is understandable because there are so many different degrees to which the brain’s biochemistry actually contributes to depression in different people, but this doesn’t mean we can completely erase its influence. For people, other factors like family history and genetics, and environmental scenarios like traumatic relationships or dangerous and unexpected events, also have a great deal of influence on how their depression came to be.

When it comes to science, the most extensively researched neurotransmitter that contributes to depression is serotonin, which is known as the Serotonin Hypothesis. Studies show that when serotonin levels are reduced centrally in the nervous system, this can lead to the development of depressive symptoms in people who are already at an increased risk of depression (14, 15, 22). Other studies have identified that serotonin receptors are less available in multiple areas of the brain in people with depression, which contributes to the serotonin hypothesis (16). Again, original antidepressants were created to increase the concentration of serotonin in the brain by blocking the action of serotonin transporters (SERT), so that serotonin would build up outside of the nerves (21).

There has been much criticism of the serotonin hypothesis over the last few decades, with many claiming it is a historical theory lacking supporting evidence (17, 19). Many have proposed that the serotonin theory was promoted by the pharmaceutical companies responsible for the development of the early antidepressants (18, 20), and have proposed that most experiments that have attempted to reduce serotonin levels to mimic depression have yielded very inconsistent results (18, 19). However, despite the confusion around the serotonin hypothesis, it is still hard to confirm that there is no influence of serotonin in the development of depression, and thus it should not be dismissed as a contributing factor.

Summary

At the end of the day, depression is far more than a simple case of feeling sad or unmotivated. It is a complex, multifaceted condition with real biological underpinnings that affect millions of people worldwide. As we’ve explored, depression encompasses various forms, including Major Depressive Disorder, Bipolar Affective Disorder, Perinatal Depression, Mixed Anxiety and Depression, and Seasonal Affective Disorder, each with its own distinct characteristics and challenges.

While the debate surrounding the serotonin hypothesis continues within the scientific community, this discussion itself demonstrates an important truth: depression is a legitimate medical condition worthy of rigorous scientific investigation and ongoing research. The fact that we may not fully understand every mechanism behind depression does not diminish its reality or the suffering it causes. Rather, it highlights the complexity of mental health conditions and the need for continued study and compassion.

Reference List:

- Depression: What is it? [Internet]. NICE CKS. 2025 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/depression/background-information/definition/

- Depression: How common is it? [Internet]. NICE CKS. 2025 [cited 2026 Feb 12]. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/depression/background-information/prevalence/

- Bains N, Abdijadid S. Major depressive disorder [Internet]. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559078/

- ICD-10 version:2019 [Internet]. Available from: https://icd.who.int/browse10/2019/en#/F30-F39

- World Health Organisation: WHO. Bipolar disorder [Internet]. 2025. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/bipolar-disorder

- Depression. Robert E Rakel [Internet]. 199AD Jun;26(2):211–24. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0095454308700034?via%3Dihub

- Carlson K, Mughal S, Azhar Y, Siddiqui W. Perinatal depression [Internet]. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/

- Perinatal mental health [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/mental-health-and-substance-use/promotion-prevention/maternal-mental-health

- Melrose S. Seasonal Affective Disorder: An Overview of Assessment and Treatment Approaches. Depression Research and Treatment [Internet]. 2015 Jan 1;2015:1–6. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4673349/

- Professional CCM. Serotonin [Internet]. Cleveland Clinic. 2025. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/22572-serotonin

- Bamalan OA, Moore MJ, Khalili YA. Physiology, serotonin [Internet]. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545168/

- Watson S. Dopamine: The pathway to pleasure [Internet]. Harvard Health. 2024. Available from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/dopamine-the-pathway-to-pleasure#:~:text=Dopamine can provide an intense,contributes to a down mood

- Bromberg-Martin ES, Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Dopamine in motivational control: rewarding, aversive, and alerting. Neuron [Internet]. 2010 Dec 1;68(5):815–34. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3032992/

- Neumeister A, Konstantinidis A, Stastny J. Association between Serotonin Transporter Gene Promoter Polymorphism(5HTTLPR) and behavioural responses to tryptophan depletion in healthy women with and without family history of depression. Archive Gen Psychiatry [Internet]. 2002 Jul;59(7):613–20. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/206543#25932352

- Hasler G. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF DEPRESSION: DO WE HAVE ANY SOLID EVIDENCE OF INTEREST TO CLINICIANS? World Psychiatry [Internet]. 2010 Oct 1;9(3):155–61. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2950973/

- Drevets W, Frank E, Price JC, Kupfer DJ, Holt D, Greer PJ, et al. PET Imaging of Serotonin 1A Receptor Binding in Depression. Biological Psychiatry [Internet]. 1999 Nov;46(10):1375–87. Available from: https://www.biologicalpsychiatryjournal.com/article/S0006-3223(99)00189-4/abstract

- Healy D. The structure of psychopharmacological revolutions. Psychiatric Developments. 1987;4:349–76.

- Lacasse JR, Leo J. Serotonin and Depression: A Disconnect between the Advertisements and the Scientific Literature. PLoS Medicine [Internet]. 2005 Nov 3;2(12):e392. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020392

- Ang B, Horowitz M, Moncrieff J. Is the chemical imbalance an‘urban legend’? An exploration of the status of the serotonin theory of depression in the scientific literature. SSM – Mental Health. 2022;2.

- Pies RW MD. Psychiatry’s new Brain-Mind and the legend of the “Chemical imbalance.” Psychiatric Times – Mental Health News, Clinical Insights [Internet]. 2020 Jun 23; Available from: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychiatrys-new-brain-mind-and-legend-chemical-imbalance

- Read J, Renton J, Harrop C, Geekie J, Dowrick C. A survey of UK general practitioners about depression, antidepressants and withdrawal: implementing the 2019 Public Health England report. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology [Internet]. 2020 Jan 1;10:2045125320950124. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125320950124

- Moncrieff J, Cooper RE, Stockmann T, Amendola S, Hengartner MP, Horowitz MA. The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Molecular Psychiatry [Internet]. 2022 Jul 20;28(8):3243–56. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-022-01661-0